|

| What remains on display of the original "Colonial Museum" is half-way down these stairs on either side of the landing. |

There is, buried in the complex of Italian museums that sit mostly unvisited in EUR (about 8 kilometers/5 miles from the Coliseum but easily accessible by metro) a "museum" that purports to display, and deal with, Italy's colonial past. Just finding this collection tells one something about the country's failure to confront its activities in northern Africa, colonial activities that stretched from the 1890s to the fall of Fascism in World War II. (encyclopedia.com has excellent historical background on the Italian colonies.)

Changes in the museum's name and location over the years underscore Italy's approach to the colonies.

|

Likely the entrance near the zoo,

before the museum acquired

its new name. |

The museum opened in 1924, in the early years of Fascism, as

Museo Coloniale, the Colonial Museum, on the Quirinale, near the seat of government, and it was designed to create pride in Italy's quests. It was not conceived of as scientific (as were similar museums in other European countries), but very much like a trade show, under the Ministry of the Colonies. There were 20 rooms, each featuring a different city or region. (There was an earlier version, dating from 1904, featuring flora from the colonies, located near a botanical institute on via Panisperna in the Monti quarter).

In 1932, the Colonial Museum was moved next to the zoo, perhaps indicating the attraction of the "exotic other," including animals like the lion. Mussolini inaugurated it with a new name a year or so later, "Museo dell'Africa Italiana" (Museum of Italian Africa). It showcased "dangerous" African fauna and the bravery of collectors, deemed "pioneers." In addition to animal trophies, there was the blood-stained uniform of General Rodolfo Graziani, known as the "butcher of Fezzan" for his brutal methods in Libya. (There's a fascinating, unsympathetic portrayal of him [by Oliver Reed] in The Lion in the Desert, an excellent 1980 film by Moustapha Akkad [Anthony Quinn plays the heroic Bedouin leader, Omar Mukhtar]. Banned in Italy when released, it was first available there in 2009 via pay TV, and now one can purchase it on DVD - worth the price.)

The museum remained closed from 1937 (ostensibly to be redesigned; there's some dispute over this date - Wikipedia [Italian] suggests it remained open until 1943) to 1947.

The museum reopened after World War II as "Museo Africano" ("African Museum"), but even then, the Italians described it (in a 1948 memo to the United Nations) as dealing with "previously unproductive tribes." It remained open until 1970, when it was essentially abandoned. There was also a major theft in 1977. None of this information appears in Wikipedia, which simply says its tutelage was "then entrusted to the Italian-African Institute, which from 1995 was reorganized as the Italian Institute for Africa and the East, both placed under the supervision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 2011 that Institute was considered defunct, and the collection (in very poor condition and without proper labelling) was transferred again to the overall Ministero dei beni culturali (Ministry of cultural works) and warehoused.

So where is it, and where are the 12,000 objects - objects of "others" gathered to be observed by Europeans - and what is its name now?

|

From EUR's central Piazza Marconi, we trooped around to

several of the museum buildings, past many entrances closed

and others open to other activities, finally to find a

temporary entrance to "the Pigorini" and a woman behind

the desk who finally knew what we were talking about. |

We had read the museum was located in the newly-reorganized complex under the overall name "

Museo della Civiltà" - which was the name of one of the several museums in EUR, and whose entrance graced the cover of our second guidebook, "Modern Rome" (that entrance now leads to the planetarium! - yes, we tried asking there about the "

Museo Africano," which the visitor desk had never heard of), re-branded as "

MuCiv" (!) and incorporating the several museums that were in EUR, including the original "

Museo della Civiltà," which has been closed "for renovations" since 2014 (and it's unfortunate that the public cannot see its great model of ancient Rome). In 2022,

MuCiv is asking the public for input on its plans for a radical refashioning of its collections. In English and Italian you can find those current plans

here and

here.

|

The entrance on our book cover

won't get you there. |

Success! of a sort. We found our way to a temporary, new entrance to another part of MuCiv, the crown jewel of the museums, Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini (known as "the Pigorini"), and after some discussion with the ticket seller, she gave us free journalists' passes, and we found what is now called the Museo Italo Africano Ilaria Alpi, or the Italian-African Museum, now named for a young Italian journalist killed in Mogadishu in 1994.

What exists are a few objects (photos right and left and below) on either side of the landing of a stairway (albeit a monumental, large stairway, photo at top of post), accompanied by some plastic sheets indicating the questions raised by retaining and showing objects collected by colonists.

The object at right is a "statuette of the Konso," "donated" by a Captain. It's hard to read the inscription (left) but it says something to the effect that "when a Konso (from SW Ethiopia) husband died, his wives were buried with him, and that this (I assume the tall statuette next to the plaque) was the tomb of a woman buried alive, according to superstition...

The object at right is a "statuette of the Konso," "donated" by a Captain. It's hard to read the inscription (left) but it says something to the effect that "when a Konso (from SW Ethiopia) husband died, his wives were buried with him, and that this (I assume the tall statuette next to the plaque) was the tomb of a woman buried alive, according to superstition...and that this was the first of the objects the Captain "astutely brought back - in 1927."

The plastic sheet hanging alongside these objects says, in Italian and English, "From the seventies of the last century up to 2017, the colonial collections had been locked in cases. They were moved, over several decades, between various institutions in Rome. The colonial Museum, and the history that it represents, were never challenged either on a museographic stage or in a public debate. Opening the cases through the collections, rescuing the latter with conservation interventions and making them accessible to the civil society are the first necessary steps so as to not allow the Italian colonial experience to be forgotten."

Italy is one of many countries confronting its colonial past. According to the panel discussion I observed at the Swiss Institute in Rome, "Erased Memories: Italian colonialism and its material legacies," it has done a very poor job so far in this regard. The scholars talked about "historical amnesia, cancelling, and the failure of Italian memory to accept" its colonial past. Waves of ex-colonial subjects, including Albanians as well as Africans, came into Italy in the 1990s, raising issues of responsibility and acceptance. The new prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, has run, like Trump, on a fiercely anti-immigrant platform. I should point out as well that while the objects were put under the auspices of the Ministry of beni culturali, the paper objects, including labels and such material as there is on provenance, were given to the National Library, according to the speakers at the Swiss Institute, which included Beatrice Falcucci who has written on "The former Museo Coloniale in Rome and beyond: colonial collections in Italy between history and the present." The separation of objects and paper does not auger well for placing the materials in their proper context. In other words, it will be difficult for Italy, given its current custody arrangements, to make the claim that it can do a better job of preserving these materials than can their places of origin.

Admittedly, this project (the objects we saw and their measly space) is a first step and is designed to let the public participate in the "unveiling." It is in fact called "Unveiled storages" and is described as "an installation that aims to place the former Museo coloniale collections at the heart of the MuCiv's museum spaces...to render objects accessible to everyone, even if only partially, that seem hidden from view and that had been hidden for several decades."

|

Above, the well-designed hall on the first floor of the Pigorini ethnographic museum.

This floor is mostly devoted to objects from Africa. |

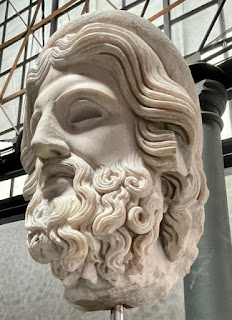

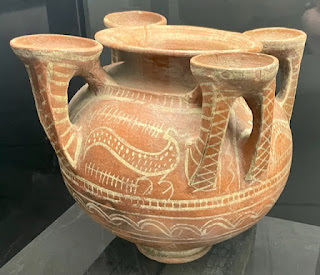

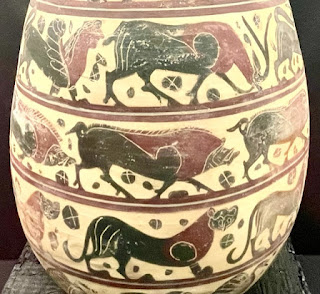

On the first floor (second floor, English style) of the Pigorini is a very high-quality exhibition of African objects collected before the Fascist era. But don't these raise similar questions? Where do they belong? Who "gave" them and why? The Swiss Institute speakers asked if there even could be a post-colonial museum. Should the main purpose be a cross-cultural approach, or preservation, or repatriation?

I've put more photos at the end of this post. The first one describes the Fascists' use of ancient Roman imagery, including colonialism; most of the rest are of the ethnographic exhibit.

|

| Certainly looks like the artworks that inspired Picasso. |

|

| A beautiful stained glass window is at the end of the large staircase. |

|

It's signed by "Giulio Rosso, dis. [designed by],

Art glass window. G.C. Giuliani, es. [the window maker]

Rome 1942 - XXI [Fascist year 21]" |

The object at right is a "statuette of the Konso," "donated" by a Captain. It's hard to read the inscription (left) but it says something to the effect that "when a Konso (from SW Ethiopia) husband died, his wives were buried with him, and that this (I assume the tall statuette next to the plaque) was the tomb of a woman buried alive, according to superstition...

The object at right is a "statuette of the Konso," "donated" by a Captain. It's hard to read the inscription (left) but it says something to the effect that "when a Konso (from SW Ethiopia) husband died, his wives were buried with him, and that this (I assume the tall statuette next to the plaque) was the tomb of a woman buried alive, according to superstition...